Connecting the new to the known: trauma-aware design meets brain-based tech

As evidence of the pandemic’s lasting impact on brain development, time perception, and mental health grows, higher ed institutions must support students with technology based on trauma-aware practices.

By Audrey Dietz

At the start of the pandemic, time defined everyone’s day differently. Some worked at home, juggling remote careers and round-the-clock childcare. Some were laid off or furloughed; others took up new hobbies or picked up gig work. Essential workers spent more time at work than ever before. Time passed in alternating bursts of monotony and rapid-fire news updates as societies mourned, pivoted, adapted, closed, opened, and pivoted again. Throughout it all, educators and institutions of higher education bore witness to change at a scale unlike anything most had seen in their lifetimes.

Arundhati Roy writes, “Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew.” In just three years, the pandemic emergency’s impact and aftermath forced a reimagining of education that has expanded the boundaries of schooling. For students across age groups – who saw their perceptions of time upended as remote learning became the norm – the experience of education and even time itself has permanently changed. This has increased the demand for educational tools that rely on pedagogical practices backed by neuroscience as a proactive approach to supporting the next generation of students.

What’s my brain AGE again?

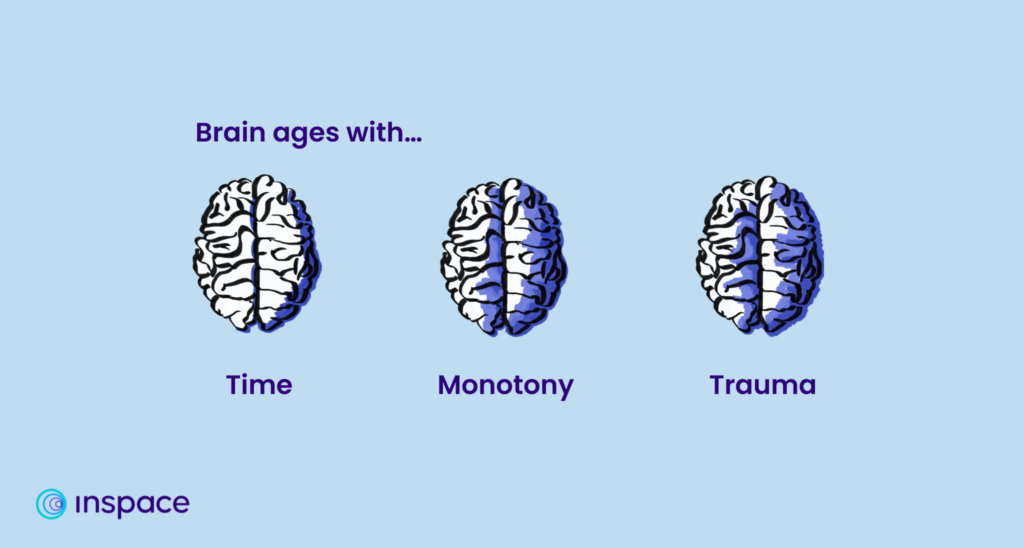

A study released on Dec. 1, 2022, by Stanford University suggests that pandemic-related stressors have changed young peoples’ brains physically, aging them several years when compared to the brains of similar peers examined before the pandemic (Gotlib et al., 2022). The researchers found “adolescents assessed during the pandemic had larger positive brain age gap estimates (brain AGE), indicative of older-appearing brains.” While skipping the immaturity of youth may sound like a positive, accelerated ‘brain age’ is typically an effect of chronic adversity and trauma.

Trauma-affected, in this case, is broadly defined as “exposure to experiences that are overwhelming; lead to strong negative emotions…and involve some degree of experienced or witnessed threat to self. A child’s inability to cope with such experiences is what sets traumatic reactions apart from […] typical responses to stressful events” (Innemee, 2015). CDC estimates that 2 in 3 young people had a trauma history before the pandemic, and experts suggest that the number is now significantly higher (Costa, 2020).

The Stanford researchers will continue monitoring teens in the study to understand the impact of accelerated brain age on the COVID-19 generation. “You have this global event that’s happening, where everyone is experiencing some kind of adversity in the form of disruption to their daily routines – so it might be the case that the brains of kids who are 16 or 17 today are not comparable to those of their counterparts just a few years ago,” co-author Jonas Miller said (Levin, 2022).

And let’s be clear: no matter what your understanding of when the pandemic ended (or will end) may be, trauma itself is understood by experts as ongoing. Institutions of higher education need campus structures that support students’ well-being sustainably – including the online platforms where they receive virtual education (Hayashida, 2022). By being mindful of the neuroscience and trauma-aware design behind technology, it’s possible to choose a meaningful future for classroom instruction with a platform that meets students where they are.

Memories of endless days

Neuroscientists and physicists have long questioned why time seems to pass differently at different stages in life, including why time seems to speed up as we age.

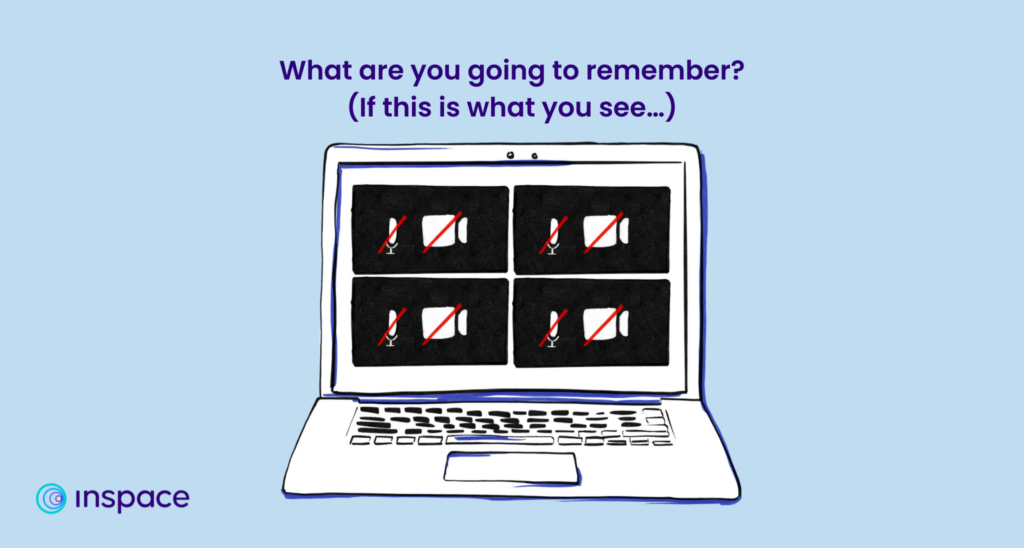

According to Dr. Adrian Bejan, older brains process time differently than younger brains (Bejan, 2019). Clock-time, measured in seconds, is not the same as mind-time, measured by changes in visual stimuli (think, frames in a motion picture, or a series of time-lapse photographs), and is unique to the individual. Dr. Bejan found that infants process many more memory frames per minute than older adults. As a result, when remembering childhood events, we recall more visual data – hence the perception that time passed more slowly in our youth. As he puts it: “People are often amazed at how much they remember from days that seemed to last forever in their youth. It’s not that their experiences were much deeper or more meaningful; it’s just that they were being processed in rapid fire” (Maizels, 2019).

So what is the result when access to milestones and awe-inducing moments is replaced with slide decks and static black squares on a screen?

According to Katherine Templar Lewis, lead scientist at Uncertainty Experts, ‘We use events as markers for time. From regular ones such as weekends and birthdays, going out to dinner, the cinema, or meeting with friends, days out. We even use the changes of scenery and pace throughout our day, such as our commute, to mark time.”

But without new experiences, new skills, and new visual input, time passes more quickly – even for young people – because the brain is exposed to fewer visual stimuli and creates fewer ‘snapshots’ in working memory. The youthful days that might have gone on forever and loomed large in memory instead zoom onward with a swipe.

Blursday, Friday, what’s the day?

Previously known mainly in trauma research, the COVID-19 pandemic brought broader awareness of temporal distortion, or the experience of time slowing down, stopping, or speeding up. This ‘blursday effect’ has been associated with heightened psychological distress in both the acute aftermath of collective trauma and over time (Holman & Silver, 1998, as cited in Holman et al., 2022).

Researchers at the University of California Irvine examined the occurrence of temporal distortion in the US during the COVID-19 pandemic. They found that 18-29-year-olds were affected more than other age groups. Pre-pandemic mental health status and lifetime trauma exposure also influenced the degree of temporal distortion (TD), and its duration. In their findings, they recommended further examination of the role of social relationships and “the pattern of associations between TD and loneliness over time” (Holman et al., 2022) as a buffer against temporal distortion.

Students can quickly feel isolated and alone in traditional online learning spaces (Blackmon & Major, 2012). This sense of isolation challenges students’ engagement, learning outcomes, and persistence. Those who take courses online often describe isolation as one of the biggest impediments to their learning, satisfaction, and success (Blackmon & Major, 2012; Rasheed, et al., 2020). While students attending classes on campus can also feel isolated, in online education, the inherent physical and temporal elements of separation can amplify feelings of isolation (Croft et al., 2015). This isolation translates to learning outcomes as well. In fact, “when people interact socially, their brains engage distinctly different neural and cognitive processes than those when they think or act alone,” according to biology and social science writer Annie Murphy Paul.

Trauma-affected students, many contending with additional mental health challenges and loneliness, are steadily marching toward the college gates. The American Council on Education’s fall 2021 survey found that 73 percent of university presidents ranked students’ mental health as their deepest concern.

Tools serving such students must include trauma-aware design features. What does this mean in the context of a virtual classroom platform? Providing an online experience that powerfully supports the brain by stimulating working memory and reignites the high-speed neural signal processing necessary for meaningful learning.

Fully commit to equity, access, and choice

The question becomes: what is needed of our virtual classrooms and gatherings in this alternate world in which we’ve found ourselves, one in which a generation-defining event is not only ongoing but also literally shaping the brains of a generation? What transformations are needed to bring students on the margins fully into our classrooms and campuses?

Furthermore, to paraphrase author and facilitator Priya Parker, what is worthy of this generation’s collective time? How can we structure classrooms and gatherings in ways that induce awe and inspire students’ brains to lay memory frames rapidly? And how do we do this in ways that outlast programming dollars and an extra hire or two? (Hayashida, 2022)

It isn’t a matter of re-engaging, re-teaching or revising the messaging. It all goes deeper. Cheryl Strayed writes of the ‘life we didn’t choose,’ and while no one chose the pandemic, a life without it is no longer ours. We can only “salute it from the shore” (Strayed, 2011). The time has come instead for a deep commitment to student equity, access, and choice in education that centers students as they are now, with the whole human selves, brains, and needs they bring to our digital campuses and classrooms. The pandemic placed constraints on teaching, illuminating gaps in educational accessibility that may not have been clear to those in power previously; now, increased accessibility is essential for institutions to continue supporting students.

Used intentionally to increase student access to services and instruction, InSpace plays a vital role in an institution’s commitment to genuinely centering students in the classroom and on the digital campus. For example, in an example cited by Learning for Justice, Professional Learning Facilitator Kimberly Burkhalter found that closed captioning, intended to serve attendees with hearing loss, improved the session experience for all attendees (Ehrenhalt, 2021). Disability activists have long described the ‘curb-cut effect,’ named for the sidewalk ramps built initially for wheelchair users that also make sidewalks more usable for everyone. Accessibility tools such as closed captioning that can be enabled, customized, and used by all participants independently from the host (as they are on InSpace) are a positive step in this area.

Context shapes the learning experience

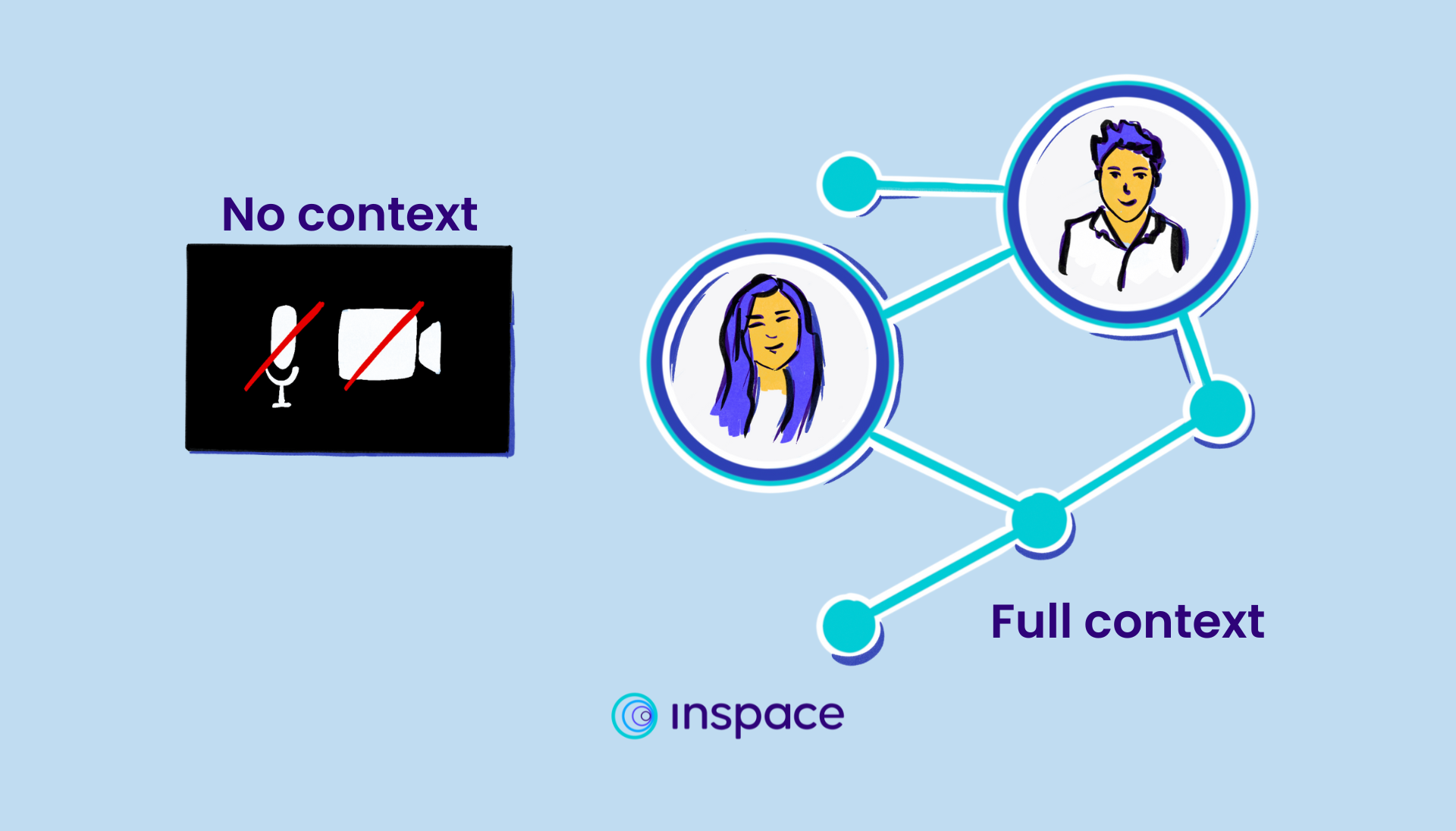

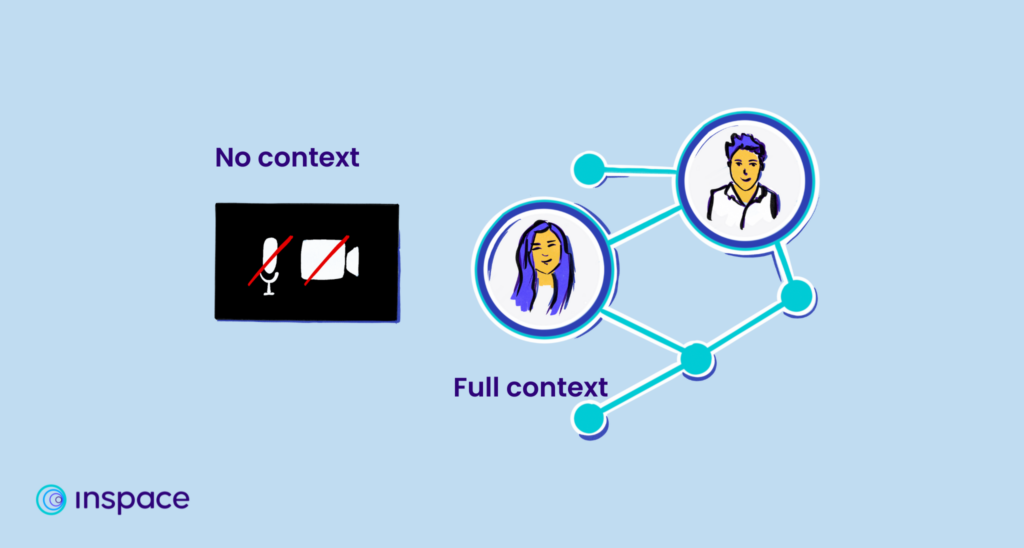

InSpace supports instructors with multiple ways to provide high-quality, meaningful visual input to support student learning. First, InSpace sessions take place in a single, visually-connected classroom session. Students have autonomy over their participation, reducing pressure to engage via limited formats pre-determined by the instructor and increasing their willingness to engage on their own terms and in multiple modes. This, in turn, can decrease student feelings of study burnout and academic disengagement (Salmela-Aro et. al, 2009; Salmela-Aro & Read, 2017). And when considering trauma-aware course design, such features support student self-regulation and allow students to focus on learning rather than managing threats to their well-being. Additionally, because InSpace provides a full-context classroom experience rather than showcasing attendee camera feeds front-and-center (where the human brain is primed to track them regardless of the classroom context), students can direct their attention where it matters most – whether that’s shared content, collaborative work, or conversations (Johnson, M. H., Dziurawiec, S., Ellis, H., and Morton, J. 1991). Seasoned educators understand that eye contact on cameras is not a marker of engagement and that universal design principles apply equally in the virtual classroom (Costa, 2020).

With InSpace, instructors can reconfigure the room settings in meaningful ways to support instruction, including breakout rooms that everyone can see and join. Students aren’t artificially isolated during group work and can move from group to group (unless an instructor chooses to lock a room). Brain research shows that social stimuli hook the brain’s attention. The human mind is highly trained to absorb social information by paying attention to everyday actions, even prioritizing the processing of such information as an automatic function separately from conscious thought (Neufeld et. al., 2016). InSpace creates an environment in which social actions and cues (such as overlapping conversations) take place, naturally motivating students to engage in the activities of the classroom. Moreover, ensuring that choice is a meaningful part of classroom procedures enhances student sense of agency and builds resilience, improving student outcomes, including for students who have experienced trauma.

As hybrid workplaces and classrooms raise questions about the impact of proximity bias, the ability for all students to connect with faculty and peers on their own terms (rather than being marooned in breakout rooms away from the action) is essential. Proximity bias stems from the natural human tendency to crave connection with others and is a consequence of the brain’s tendency to assign outsize importance to rapport built through close interaction – and out of sight is out of mind (Tsipursky, 2022). Rather than being confined to a blank screen or an unchanging view of black squares, especially during group work in breakout rooms, students working with InSpace see an ever-evolving view of the classroom that shifts in response to what is being taught and the activities taking place in class.

Make learning visible

While facilitating instruction on InSpace, educators can customize and change the space backgrounds with two clicks, ensuring visual input is relevant to what is being taught. As the brain is prompted to process extra frames throughout the learning process, the students avoid the monotony of repetitive tasks and the negative impacts on mental health, major stress, and chronic boredom that can accompany them (Bejan, 2019; Johansson, 1989; Willis, 2014). From providing quick environment changes (beach break, anyone?), to designing intricate pedagogically-aligned backgrounds filled with relevant instructional cues for students, backgrounds in InSpace are limited only by the imagination. InSpace is built upon the longstanding educational theories of Paivio (1991), relying on the power of dual coding and visual imagery to help students make meaningful connections to the material presented in the classroom.

Combining InSpace’s movement, proximity audio, and collaboration features, peer instruction – where students are the sense-makers in their learning process – is also just a click away. The virtual learning environment shouldn’t leave students wondering whether their peers are engaged with the lessons or thinking critically during class time – the classroom should be designed to make learning visible and support students in carrying a rigorous cognitive load during class time rather than ‘sitting and getting.’ InSpace offers instructors the teaching tools they need to meet students’ learning moves with intentional responses and strategies. InSpace, in other words, is a place where students can master the metacognitive strategies necessary for success within the disciplines they pursue. There is room here for productive struggle, which grows brainpower (Means & Knapp, 1991; Ritchhart, 2002).

As higher education institutions assess their own student-readiness for the next wave of enrollments, it will be crucial to engage learners using technology designed with trauma-aware practices in mind. Emerging now is the essential need for tools that revitalize students’ relationships to learning and that reignite the centers of the brain that crave novelty, challenge, and human connection – while satisfying increased student demand for flexibility, access, and affordability via online education. At InSpace, we transform virtual communication and collaboration with an intuitive, immersive platform that connects people globally, empowering them to achieve their potential through accessible innovation.

Curious to experience the InSpace difference? See for yourself.

Avnet, T., & Sellier, A. (2011). Clock Time versus Event Time. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 47(3).

Blackmon, S.J., & Major, C. (2012). Student Experiences in Online Courses: A Qualitative Research Synthesis. Retrieved December 2, 2022 from https://www.cu.edu/doc/student-experiences-online-classesqual-study.pdf.

Blackwell, A.G. (2017). The Curb-Cut Effect. Stanford Social Innovation Review. Retrieved February 7, 2023 from https://ssir.org/articles/entry/the_curb_cut_effect.

Burkeman, Oliver. (2021) Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals. Penguin Canada.

Clark, J.M., & Paivio, A. (1991). Dual Coding Theory and Education. Educational Psychology Review. 3(3).

Costa, K.R. (2020). Cameras be Damned. Retrieved February 7, 2023 from https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/cameras-damned-karen-costa/.

Croft, N., Dalton, A., & Grant, M. (2010) Overcoming isolation in distance learning: Building a learning community through time and space. Journal for Education in the Built Environment, 5(1), 27-64.

Ehrenhalt, J. (2021). Learning Virtual Redefined. Teaching for Justice. Retrieved February 7, 2023 from https://www.learningforjustice.org/magazine/fall-2021/learning-virtually-redefined.

Gotlib, I. H., Miller, J. G., Borchers, L. R., Coury, S. M., Costello, L. A., Garcia, J. M., & Ho, T. C. (2022). Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and brain maturation in adolescents: Implications for analyzing longitudinal data. Biological Psychiatry Global Open Science. Retrieved December 2, 2022 from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpsgos.2022.11.002.

Hayashida, M. (2022). “A Broader Way of Thinking About Well-Being.” Retrieved December 5, 2022 from https://www.insidehighered.com/views/2022/12/05/broader-way-thinking-about-well-being-opinion.

Holman, E. A., Jones, N. M., Garfin, D. R., & Silver, R. C. (2022). Distortions in time perception during collective trauma: Insights from a National Longitudinal Study during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. Retrieved December 2, 2022 from https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0001326.

Johansson G. Job demands and stress reactions in repetitive and uneventful monotony at work. Int J Health Serv. 1989;19(2):365-77. doi: 10.2190/XYP9-VK4Y-9H80-VV3K. PMID: 2714928.

Johnson, M. H., Dziurawiec, S., Ellis, H., and Morton, J. 1991. Newborns’ preferential tracking of face-like stimuli and its subsequent decline. Cognition 40:1–19. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(91)90045-6

Levin, D. (2022).“Pandemic stress physically aged teens’ brains, a new study finds. Stanford News. Retrieved December 5, 2022, from https://news.stanford.edu/2022/12/01/pandemic-stress-physically-aged-teens-brains-new-study-finds/.

Levine, R. (1997). A geography of time: The temporal misadventures of a social psychologist, or how every culture keeps time just a little bit differently. New York: Basic Books.

Maizels, R. (2019). No, It’s Not Just You: Why time “speeds up” as we get older. SITN Blog. Retrieved December 2, 2022, from https://sitn.hms.harvard.edu/flash/2019/no-not-just-time-speeds-get-older/.

Means, B. & Knapp, M.S. (1991). Rethinking teaching for disadvantaged students. In B. Means, C. Chelemeer, & M.S. Knapp (Eds.), Teaching advanced skills to at-risk students: Views from research and practice (pp. 1-26). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Melidona, D., Taylor, M., & McNamee, T.C. (2021). 2021 Fall Term Pulse Point Survey of College and University Presidents. ACE American Council on Education. Retrieved December 15, 2022 from https://www.acenet.edu/Research-Insights/Pages/Senior-Leaders/Presidents-Survey-Fall-2021.aspx

Neufeld, E., Brown, E.C., Lee-Grimm, S., Newen, A, & Brüne, M.(2016). Intentional action processing results from automatic bottom-up attention: An EEG-investigation into the Social Relevance Hypothesis using hypnosis. Consciousness and Cognition, 42, 101-112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2016.03.002

Parker, P. (2018). The Art of Gathering. New York: Riverhead Books.

Paul, A.M. (2021). The Extended Mind: The power of thinking outside the brain. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Rasheed, R. A., Kamsin, A., & Abdullah, N. A. (2020). Challenges in the online component of blended learning: A systematic review. Computers & Education, 144, 103701.

Ritchhart, R. (2002). Intellectual character: What it is, why it matters, and how to get it. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Roy, A. (2020). The pandemic is a portal. Financial Times. Retrieved February 7, 2023 from https://www.ft.com/content/10d8f5e8-74eb-11ea-95fe-fcd274e920ca.

Salmela-Aro, K., Kiuru, N., Leskinen, E., & Nurmi, J.-E. (2009). School burnout inventory (SBI). European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 25(1), 48–57. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759.25.1.48

Salmela-Aro, K., & Read, S. (2017). Study engagement and burnout profile among Finnish higher education students. Burnout Research, 7, 21–28.

Strayed, C. (2011). “Dear Sugar, The Rumpus Advice Column #71: The Ghost Ship That Didn’t Carry Us.” Retrieved December 7, 2022 from https://therumpus.net/2011/04/21/dear-sugar-the-rumpus-advice-column-71-the-ghost-ship-that-didnt-carry-us/.

Tsipursky, G. (2022). What Is Proximity Bias and How Can Managers Prevent It? Harvard Business Review. Retrieved February 7, 2023 from https://hbr.org/2022/10/what-is-proximity-bias-and-how-can-managers-prevent-it.

Willis, J. (2014). Neuroscience Reveals That Boredom Hurts. Phi Delta Kappan, 95(8), 28–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/003172171409500807